History of Kos

Historical review of Kos island

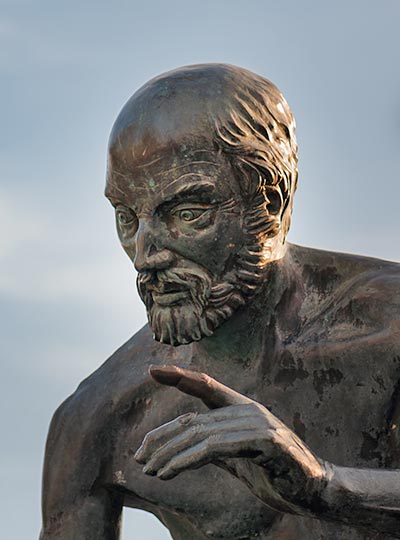

The long and illustrious history of Kos has etched a route across the ages, beginning in the third millennium BC, at the end of the Neolithic Age (a period which lasted roughly 3,500 years, i.e. from 6,500 BC to 3,000 BC). From the few remains of the first buildings excavated from that period all the way to our present age, time has left its unmistakable mark in its wake, in the form of houses, monuments and other buildings and objects crafted by human hands. Kos has its own special place in Greek Mythology as well. According to legend, the island was the setting of the famed battle between the Olympian Gods and the Giants (the so-called “Gigantomachy”), while it was here that Hercules and his comrades came to found the Heracleidae dynasty, of which Hippocrates is a distinguished descendant.

In addition to the deeds of mythological heroes, Kos was historically also significantly influenced by a succession of great civilizations, including the Minoan, Mycenaean and Dorian, from around 1100 BC to approximately 600 BC. During this period, the island flourishes while unwaveringly responding to threats with war, and changes its system of governance from a monarchic to an oligarchic system.

In 546 BC Kos is conquered by the Persian Empire, and remains its subject until 478 BC, when it becomes part of the Delian League (an association of Greek city-states led by the Athenians), and a free city-state once again. In the years that follow, Kos allies itself with the Peloponnesian League (a military coalition of Greek city-states led by the Spartans), in a period marked by civil wars and political unrest. It is during this time that the homonymous capital of the island of Kos is founded, which remains to this day its capital city.

The Rise and the Fall.

In 288 BC Kos becomes a member state of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, maintaining high privileges bestowed upon them by the conquering Ptolemy dynasty. The island experiences a period of prosperity for approximately 100 years, ending with the Roman invasion of 197 BC, a period characterized by the erection of the great temple of Asclepius among other important monuments.

The later Byzantine occupation of the island witnesses the destruction of all non-Christian monuments, while successive earthquakes and continual invasions lead to the island’s gradual decline, which culminates in the final blow: the abandonment of the famed temple of Asclepius. However, in the 11th century AD, Kos regains prominence, this time as one of the Aegean’s most important harbors, as a result of the development of trade in the eastern Mediterranean. From 1309 to 1314, the Byzantines hand over the island’s administration first to the Knights of St. John and then to the Knights Templar. This period witnesses the building of fortification works on the island, including the castle in the city of Kos and that of Antimachia.

1523 marks the beginning of the Ottoman occupation of the island, which often finds itself prey to attacking Algerian and Venetian invaders, among others. The centuries that follow are characterized by the harshness of the Ottoman occupiers despite the fact that the island’s harbor is at that time a crucial stop for trade ships traveling between the West and the Ottoman Empire.

The Road to Unification with Greece

The Turks withdraw in 1911 and their place is taken by the Italians, who gradually occupy not only Kos, but the rest of the Dodecanese Islands as well. The Dodecanese are officially annexed to Italy as part of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, and the inhabitants of Kos become Italian citizens but without voting rights. World War II finds Kos first under occupation by the Germans, who then hand over the island to the English (following the former’s defeat), who in turn set up temporary military administration of the island. Finally, in 1946, Kos and the rest of the Dodecanese Islands are annexed to Greece as dictated by the Allies (USA, USSR, Great Britain and France). The unification is officially signed on March 7, 1948.